Thanks to the research on these mummies, many hidden questions about the Quanche culture have been able to be answered

From the cliffside path that leads down to the sea, about four kilometersaway, I come to a halt. This is the spot: a cave, its entrance barely visible. Ilook up at the looming face of the rock. I sense it staring back at me,beckoning with its stash: hundreds of caves, built over the centuries fromthe lava flows of Mount Teide.

Any one of them could be the cave we’relooking for—here, history has not yet been written.Within this gorge in southern Tenerife, the largest of Spain’s Canary Islands,a stunning cave was found in 1764 by Spanish regent and infantry captainLuis Román. A contemporary local priest and writer described the find in abook on the history of the islands: “A wonderful pantheon has just beendiscovered,” José Viera y Clavijo wrote. “So full of mummies that no lessthan a thousand were counted.” And thus the tale of the thousand mummieswas born. (Read about the different types of mummies found worldwide.) Few things are more exciting than navigating the ambiguous edge betweenhistory and legend. Now, two and a half centuries later, in the gorge knownas Barranco de Herques—also called “ravine of the dead” for its funerarycaves—we find ourselves in the place that most local archaeologistsconsider to be the mythical “cave of the thousand mummies.” There are nowritten coordinates; its location has been passed on by word of mouthamong a chosen few. The hikers who venture along the path are abivious to its existence

In the company of islander friends, I feel privileged to be shown the placewhere they believe their ancestors once rested. I crouch toward the narrowopening, turn on my headlamp and drop to the ground. To find this hidden realm, we crawl in on our stomachs for a few claustrophobic meters. Butthere’s a reward for subjecting ourselves to the tight squeeze: a tall, spaciouschamber suddenly opens before me, holding the promise of a journey to theisland’s past.“As archaeologists we assume that the expression ‘thousand mummies’ wasprobably an exaggeration, a way to suggest that there were indeed a lot, awhole lot—hundreds,” says Mila Álvarez Sosa, a local historian andEgyptologist.

In the darkness, our eyes slowly adjust. We survey the spacefor the telltale signs of a necropolis in the meandering lava tube, part of anextensive system across the island.These weren’t the first mummies to be unearthed on the island. Butaccording to local lore, a large sepulchral cave like this one held thepantheon of the nine Mencey kings who ruled the islands in precolonialtimes.The cave’s location was a scrupulously guarded secret.

And there was norecord of it, which only served to elevate it as the holy grail of Canarianarchaeology. Locals maintain they don’t disclose the location in order toprotect the memory of their ancestors who rested there, the Guanches, theIndigenous people of this island—no distinct Guanche population remainstoday. Others say it was lost to a landslide, buried forever. (Go beyond thebeaches in the Canary Islands.)What may have been a certainty for those 18th century explorers morphedinto legend when the mummies were plucked from their resting place andtheir location was lost. But the precious few—from that cave and others—that remain intact and are held in museum collections are helping scientistsunravel the story about the archipelago: when and where the first inhabitantscame from, and how they honored their dead.

Preserving the deceased for eternityTenerife was the last island in the archipelago to fall to the Castilian crown,beginning in 1494. It wasn’t the first confrontation the islanders had withEuropeans, but it would be the last. Álvarez Sosa imagines the stark contrastwhen at the end of the 15th century, the dawn of the Renaissance, soldierssailed in on ships and wielded swords on horseback. They came face to facewith a people just emerging from the Neolithic era, cave dwellers who woreanimal skins and used tools made of sticks and stones. “But yet theyhonored their dead, preparing them for their last trip,” Álvarez Sosa says. They preserved them

A fascination with death led the colonists to chronicle the funerary ritual indetail. “That’s what mainly caught the attention of the Castilian conquerors,”says Álvarez Sosa. In particular, they were intrigued by the embalmingprocess—mirlado—that prepared the xaxos, as the Guanche mummies werecalled, for eternity.

The cave walls are silent. Submerged in the darkness, I imagine the awe LuisRomán must have felt when, imbued with the spirit of the Enlightenment andaccompanied by locals, he entered the necropolis on a mission to retrieve afew specimens for study. He transported the bodies to Europe where, by the18th century, mummies represented a scientific curiosity as well as anovelty; both scholars and collectors took an interest.

I picture the moment Román raised his torch, revealing hundreds of bodiesfrozen in time. He must have been overcome by a mixture of sacrilege andexhilaration. Curiously the writer who summarized a report of their visitomitted the location. If the intention was to preserve the cave from plunder,he regrettably failed: by 1833 multiple sources confirmed no bodiesremained. (Learn more about Egypt’s royal mummies.)

I stand up and shake the white dust from my hands and knees. My headlampdimly illuminates the walls. Though I know there’s not even a remotepossibility, in my heart I still long to spot a xaxo (pronounced haho) in somenook or cranny, just like Viera y Clavo described.The method for preserving these corpses for their battle against time andnature was surprisingly simple. “It’s the same process you would use withfood,” says Álvarez Sosa. “The bodies were treated with dry herbs and lardand were left to dry in the sun and smoked by fire.” It took 15 days to preparea xaxo, compared with 70 for an Egyptian mummy (40 days to dehydrate innaturally occurring natron salt, then 30 days of embalming in oils and spicesbefore the cavity of the corpse was filled with straw or cloth and wrapped inlinen). Another key difference: according to chronicles, for propriety women and18th centuries the mummies were a lure for the European cultured classes.Our xaxos traveled around the world to be placed in museums and privatecollections, and some were even ground into aphrodisiac powders.”Others might have ended up at the bottom of the sea, Álvarez Sosa posits inher book Tierras de Momias (Lands of Mummies), probably thrownoverboard when balmy conditions on the ship activated the decompositionprocess during the trip to the Continent. (What surprising new clues are revealing about ancient bog mummies

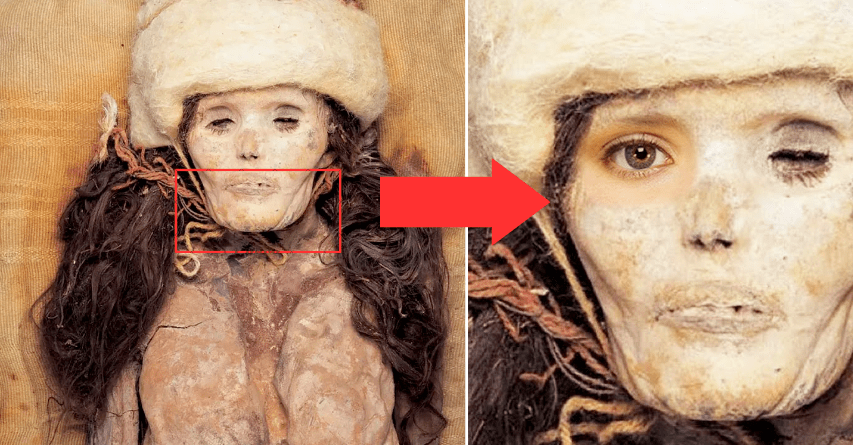

Despite having the intact Guanche mummy and remains of three dozenmore, we know very little about their tombs. “No archaeologist has everfound a xaxo in its original environment,” María García explains.A CT scan performed in 2016 on the same mummy—the best example of the40 in museum collections—in a Madrid hospital allowed researchers to peerinto its interior without damaging its structure.

This is not the first time I traveled to the Canaries seeking answers. Eightyears ago I rappelled down a cliff face in the gorge, peering into a dozencaves in search of the legend. I reread 15th- and 16th-century chronicles andinterviewed experts to unravel the origins of the early Canarians.These were the mythical Fortunate Isles where ancient Mediterraneanseafarers had once landed. The Europeans who later encountered theislands in the Middle Ages found that unlike other Atlantic archipelagos,these islands were inhabited, their populations seemingly isolated forcenturies.Chronicles spoke of tall Caucasians, which sowed the seeds for now refutedhypotheses: they alternately descended from shipwrecked Basque, Iberian,Celtic, or Viking sailors. I left the island without coming much closer to anyanswers. But now modern technology has put an end to the enigma that lasted for centurise. The Mummies have spoken

place, the city’s National Archaeology Museum. One night in June 2016under tight security the mummy was taken on its shortest outing ever: to anearby hospital for a CT scan.“We had already had CT scans of several Egyptian mummies,” says JavierCarrascoso, associate chief of radiology at Madrid’s QuirónSalud UniversityHospital, which offered to extend the technology to the Guanche mummy.The scan provided data that debunked a hypothesis that they had simplydehydrated naturally as well as the theory that the Guanche mummificationprocess was derived from Egypt, some 3,000 miles away. (Learn howmummies show clues to ancient diseases.)“It was impressive,” says Carrascoso. “The Guanche mummy was muchbetter preserved than the Egyptian [ones].” The definition of its musclescould still be observed, and the hands and feet in particular were outlined indetailed relief. “It looked like a wooden sculpture of Christ,” he says.But the most remarkable finding was hidden: unlike its Egyptian counterpart,the Guanche mummy had not been eviscerated. Its organs, including thebrain, were perfectly intact thanks to a mixture—minerals, aromatic herbs,bark of pine and heather, and resin from its native dragon tree—that haltedbacteria and thus decay, inside and out. Radiocarbon dating in 2016 revealeda tall, healthy male, perhaps a member of the elite, given the condition of his hands feet and teeth